Risk and Return in a New Regime

“The stock market is a no-called-strike game. You don’t have to swing at everything – you can wait for your pitch."

Warren Buffett

Just as batters can discern the best time to take a swing to maximize their chances of successfully hitting a pitch, we believe in managing risk over return, prioritizing patience and capital preservation, especially in uncertain times.

Our Capital Markets Forecast is the foundation of our investment process. This annual research piece contains seven-year projections that form the basis of strategies we design to help you achieve your goals.

The forecast, designed to manage risk and maximize opportunities, provides the quantitative blueprint for the steps we foresee — at today’s starting point and beyond.

Risk & Return in a New Regime

During the 40 years between early 1982 and early 2022, capital markets experienced more tailwinds than headwinds, largely due to the support of global central banks. Pumping money into the economy created less uncertainty in markets, enabling growth in global economies and capital markets. All of this was relatively sustainable as long as inflation remained subdued. However, with inflation at untenable levels, global central banks, most notably the Federal Reserve, have pivoted their stances, raising global short term interest rates to levels not seen since the 1990s internet bubble burst.

In last year’s Capital Markets Forecast, we discussed the idea that we were amid a paradigm shift in markets and that trends were changing in relation to what markets had experienced since 2009. This year, we posit that the prior regime was even more entrenched than we had previously insinuated. We believe the economy is headed to an adjustment period to flush out excess cash from the economy, creating more uncertainty than that to which people have become accustomed. In this investing landscape, we believe a defensive and more discerning stance is paramount to avoid extreme volatility and/or capital impairment. It should not be inferred from this that there will be no investment opportunities; on the contrary, there should be many. However, capitalizing on these opportunities will likely be less about “riding the market wave” and more about judiciously picking our spots in public and private markets.

Normal Monetary Policy Regime (pre-2008)

To understand how we arrived at our current uncertain, inflationary environment, and to illustrate how lending rates contribute to market tailwinds and headwinds, we need to go back to the 1970s. In 1972, inflation was close to The Federal Reserve’s (the Fed’s) target of 2%, with a year-over-year Consumer Price Index (CPI)[1] of 2.7%. CPI quickly increased over the next few years, climbing to 6.0% in 1973, then 10.9% midway through 1974, and finally reaching a cyclical peak of 12.9% in December of 1974.

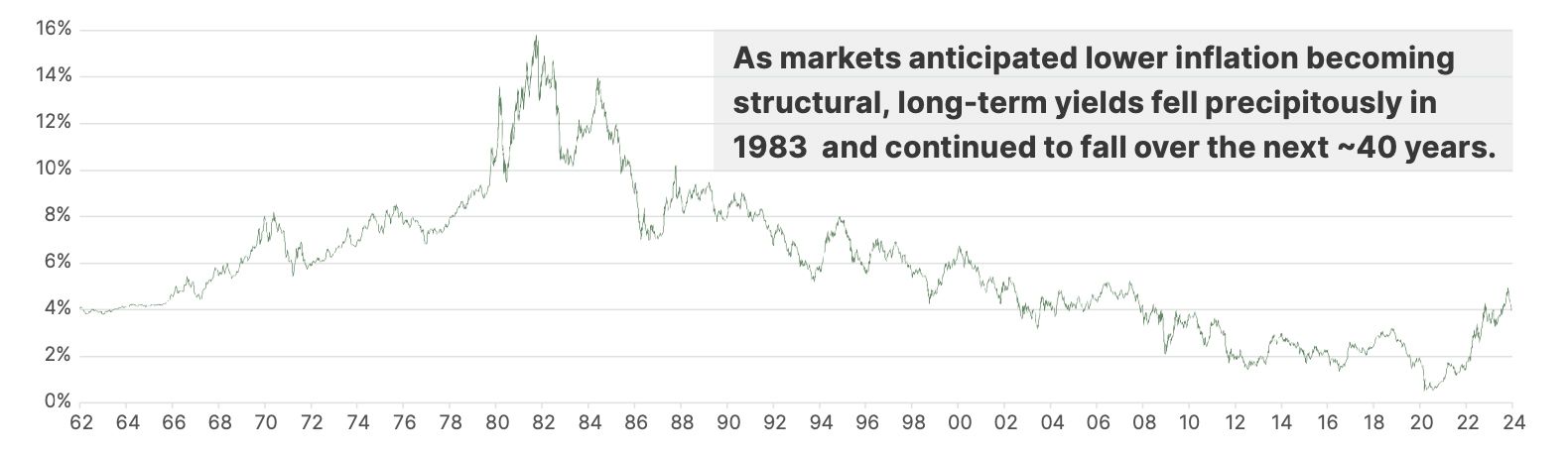

Central bank lending rates shape the market environment, significantly contributing to tailwinds and headwinds. In sluggish markets, low lending rates create tailwinds by catalyzing credit expansion, lowering the cost of capital for businesses, and increasing asset values, creating a wealth effect that encourages additional spending. In overheated markets, high lending rates do the opposite, generally serving to stultify the economy and the markets. Thus, over the next seven years, the Fed waged an arduous battle against inflation, culminating in Paul Volcker’s Fed Funds rate of 20% in July 1981. By 1983, inflation was down to 2.5% from over 10% merely 18 months earlier. As markets anticipated lower inflation becoming structural, long-term yields fell precipitously during that period and continued to fall over the next ~40 years (Figure 1 and associated data).

FIGURE 1. A History of 10-Year Treasury Yields (1962 - Present)

Circumstantial evidence in both of these periods suggests that rising rates were a headwind during the earlier period and a tailwind in the later period. In fact, one could suggest — though not say definitively — that the underlying rate environment was THE most important factor behind those respective market trends (i.e., stagnation in the former, ascension in the latter).

This period of time is what we would consider a “normal” monetary policy regime – the Fed was appropriately loose and tight with monetary policy, closely monitoring the market to keep it in equilibrium by adjusting rates as needed.

Abnormal Monetary Policy Regime (2008–2021)

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) ushered in a new regime. In its aftermath, central banks worldwide feared deflation, so they lowered interest rates to 0% and sharply expanded their balance sheets to support asset prices. During the 11 years from March 2009 through February 2020, the S&P 500 rose over 400%, for an annualized total return of 18.3%. Over the next 13 years, interest rates crept up slightly, though nowhere near enough to offset economic expansion.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, the equity market crashed 34% during a 5-week period from mid-February to late March. Global central banks responded by resuming 0% interest rates and expanding their balance sheets even more than they had during the GFC. In addition, the government enacted tremendous fiscal stimulus at the same time.

Typically, we would expect inflation to result from such a low interest rate environment; however, because inflation had been avoided so far, central banks were not concerned about the impact of keeping lending rates low. In 1993, legendary investor Sir John Templeton famously wrote:

“The investor who says, ‘This time is different,’ when in fact it’s virtually a repeat of an earlier situation, has uttered among the four most costly words in the annals of investing.”

Sir John Templeton

Accordingly, the incredible monetary and fiscal stimulus triggered long-dormant inflation that we would have expected to appear at some point over the prior decade.

As a result of this inflation and central bank policy reversals — with rates increased from 0% at the beginning of 2022 to 5.5% at the time of writing — it is highly likely the era of uber-loose monetary policy we experienced during the 13+ years from 2008–2022 is over.

- High Inflation means global central banks will not lower interest rates in the near term, and certainly not to the levels experienced over the last decade plus. Although recent inflation readings are well below the highs experienced in the summer of 2022, they are still far away from the Fed’s targeted 2% rate — with the proverbial “last mile” in the fight potentially the most difficult part. So, even if the Fed continues to pause at the top, that does not suggest that substantially lower rates are imminent.

- Central bank balance sheets remain bloated (especially the Fed’s) meaning there still remains too much money in the economy, which is inherently inflationary. Assets rocketed from ~$4 trillion to ~$9 trillion from 2020-2022. For perspective, before the GFC, the balance sheet was under $1 trillion! So, a lot of asset unwinding has to be done to get to some level of normalcy. And as the assets roll off the balance sheet via maturity, liquidity will come out of the economy and the markets. While contracting the balance sheet will certainly abet the Fed in its goal to get inflation back closer to its 2% goal, it will also affect both the economy and the capital markets.

- Reversal of globalization. In the aftermath of the pandemic and the resulting supply chain disruptions, the U.S. market began a shift to onshoring much of its manufacturing demand. Additionally, any residual globalization is moving closer to home. Geopolitical headwinds in the Middle East and Eastern Europe continue to increase, which will likely serve to accelerate the reversal of globalization. This could further add to existing inflationary pressures.

A New Regime: A Return to Normal Monetary Policy (2021 – )

John Kenneth Galbraith suggested a phenomenon called the “extreme brevity of the financial memory,” suggesting that there is a strong recency bias in the most recent of cycles to the exclusion of past cycles that behaved differently. In fact, he states emphatically “There can be few fields of human endeavor in which history counts for so little as in the world of finance. Past experience, to the extent that it is part of memory at all, is dismissed as the primitive refuge of those who do not have the insight to appreciate the incredible wonders of the present.”

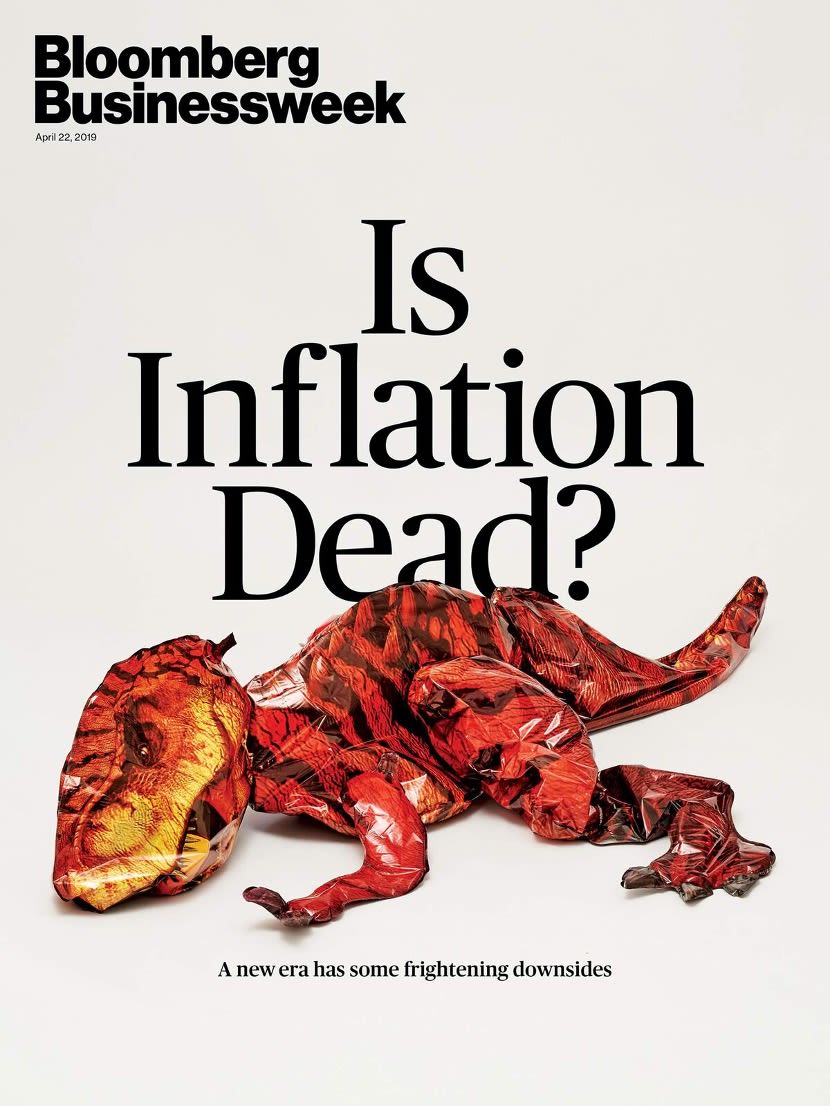

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, as the bull market was celebrating its tenth anniversary, many people thought this time was different – that recessions would no longer impact the stock market in a meaningful way, Quantitative Easing (i.e., QE) was a new paradigm that would prevent market and economic declines, government debt and deficits did not matter, and of course, inflation might be gone for good (Figure 2).

Irrespective of the direct effect of the coronavirus pandemic on the economy, we see over the last two years that such comments were clearly unfounded given the impact of debt, deficits, and inflation in the economy and capital markets.

In other words, this time isn’t different – after the low rate environment experienced until early 2022, we know we’re entering a period marked by greater uncertainty in monetary and fiscal policy as the market seeks to return to balance.

FIGURE 2. Is Inflation Dead?

This magazine cover from Spring 2019 suggests that, like the dinosaurs, inflation is extinct.

A Bumpy Transition

Recently, statements from the Fed have indicated more uncertainty than usual.

Of course, the Fed is focused more on the economy than on financial markets. As investors, we see their view on uncertainty translating to capital markets. In general, market uncertainty looks like a market with less clear direction and with more day-to-day volatility.

As investors, we see the market expressing the excess uncertainty in the form of valuation and the associated equity risk premium, which measures the compensation investors receive to take on risk in the equity market in the form of return over and above the risk-free rate (e.g., the rate on U.S. Treasury bonds). When the excess risk premium is high, investors are fearful, and thus, the market offers large compensation for investors to take risks; conversely, when it is low, the market is relatively complacent and, as a result, offers little in excess premium for compensation. Figure 3 shows the last time Excess Risk Premium was at this level – 2007, 2002, and 1998 – periods with relatively meager subsequent 7-year returns (the jury is still out on 2019, as we are still in that 7-year period).

FIGURE 3. Excess CAPE Yield (1950 - 2023)

Historically, when Excess CAPE yields have been low, the coming years have not been an auspicious time to invest in the equity markets.

Source: Robert Shiller and Balentine

In summary, looking at the recent history of U.S. monetary policy, the Fed’s ability to get inflation consistently under 2% starting in 19972 was an underappreciated, tremendous feat that not only validated the “Great Moderation” monetary policy that had been in place since 1982, but also brought about a major fiscal policy tailwind for the next two decades. Low inflation meant interest rates could remain low, which allowed the Treasury to run higher deficits while maintaining a similar debt servicing cost – in other words, the government could increase deficits owing to lower underlying interest rates. As a result, a combination of lower taxes and higher government spending allowed for a ballast if the economy encountered some turmoil.

No one could have projected that era could last for over two decades, but that indeed happened. At this point, it is our belief that this structural fiscal policy tailwind is now over, with higher interest rates and effectively no capacity to take on additional debt, especially in light of recent downgrades of the U.S. government by ratings agencies.

What Does This Mean for Investors in the Near-Term?

- Investors may expect modest returns from equities, but they should also expect more volatility than experienced in the recent past. Additionally, the disparity between the volatility in equities and the volatility in bonds is likely to increase.

- Interest rate movements and bonds may be more volatile than during the post-GFC period, although likely less volatile than experienced during 2022-2023. Importantly, however, the yield component of the bond's total return is now high enough to ameliorate much of that volatility and still allow for modest returns, especially on a risk-adjusted basis compared to equities. In other words, when interest rates are close to zero, the vast majority of the return of the bonds comes from capital appreciation and depreciation. However, now the yield component may serve as a nice return buffer, generating income to either supplement capital gains or offset capital losses, making overall bond returns more palatable. So, it's important to remember strong equity returns occur in concert with strong returns from bonds on both an absolute and risk-adjusted basis.

- Unlike many prior years, there are solid cash yields, which means that cash can be strategic in terms of immunizing against needs in the short term, and clients can begin to think about immunizing for medium-term needs as well. In other words, cash can be used strategically to immunize in an environment with inflation uncertainty and a Federal Reserve that has articulated the desire to have real positive yields of 1.75%-2% (though, of course, this goal of theirs is subject to change at any moment, either higher or lower, as economic conditions change).

- Because we expect more volatility, it is important for investors to remain discerning within public markets. To be sure, there will be opportunities within stocks and bonds, however, capturing those will require more tactical management and a willingness to be opportunistic. Overall, a more prudent spending policy in tandem with the right portfolio diversification should serve to allow investors to continue to achieve their goals despite the potential headwinds in capital market returns.

_________________

1The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. Evaluating the change in CPI over time can provide real-time insight into inflation le

2 To be fair, inflation reached that level in 1986 for some months, but this was more due to base effects, coming off higher inflation in the many years early, and was not sustainable.

Browse our collection of resources from trusted thought leaders.

Balentine experts offer their authentic take on the latest financial topics, including our exclusive market publications, news, community events, and more.

%20(1).png)

.png)

.png)

%20(1).png)